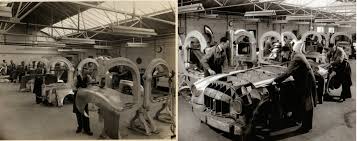

The English wheel was primarily used for as a metalworking tool that enables a craftsperson to form rigid shapes and compound curves from flat sheets of various metal. The process of using an English wheel is known as wheeling. Wheeling came into its own during WWII building aircraft skins and lead right into custom and performance vehicles. English wheels are primarily shaping machines but with the correct skill and imagination can form panels, throw body lines, make finish trim work. An illusion that the English wheel takes magical powers to operate is in truth as random as combing your hair. John Glover told stories of women/children cutting and shaping panels to wooden bucks at the De Havilland Aircraft Company a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in Hertfordshire. De Havilland was responsible for several important aircraft which revolutionized aviation and was instrumental in England’s defense. Over the years I got the opportunity to meet the mature version a lot of the WWII youth that worked in the factories, 100’s of English wheels making panels as fast as and as close as possible, I was told that as long as the edges touched, they could be riveted. As I got into the restoration game, I realized that the early aircraft and automobile panels were not as precision as the fabricators today convince their customer base they are. The fantasy of perfect cars, turned into the reality that they were one-off rides more like snowflakes than precision machines. Raising panels by surface stretching using any panel beating or shaping processes allowed dead soft materials provided by manufacturers to take rough shapes then be planished to desired shapes. This process was used wherever low volumes of deep compound curved panels are required, typically in coachbuilding, car restoration, spaceframe chassis racing cars that meet regulations that require sheet metal panels resembling mass production vehicles (NASCAR) car prototypes and aircraft skin components. Deep panel processes unitize a combination of English wheel shaping and shrinking the edge by stack shrinking and or mechanical gathering. Mechanical gathering can put stress risers in lightweight materials a no-no for long term applications.

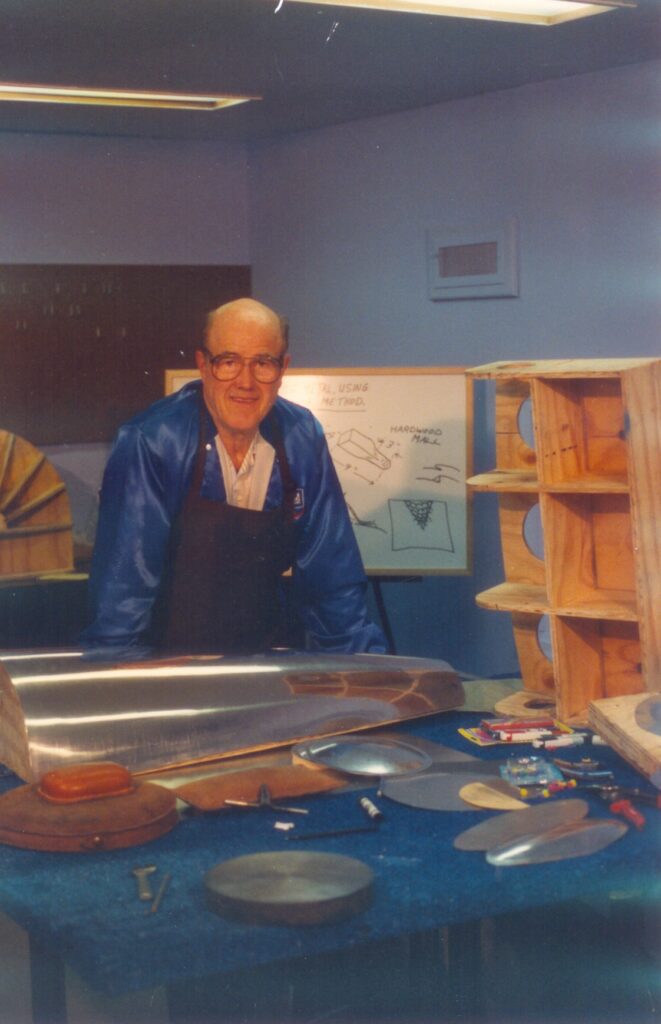

In 1985 I moved to Kannapolis to join Baker Schiff Racing as a fabricator, I discovered a book written by Ron Fournier, I got a copy for my dad early in 1986, we were working on starting our own fab shop and the book was a great reference. The 1980-1988 cup cars were bondo buggies at best, most of the metal work was challenged, aero treatments were bondo. My dad Cal Davis was quick to embrace metal shaping as a solution, the associated equipment and skills was his mission. In the 1984 version of the Ron Fournier book was an address to a gentleman named John Glover that had a set of plans for $10 a 48” English wheel. After many phone conversations about the English wheel and metal shaping in general my dad and John Glover became lifelong friends in fact my dad manufactured the Metal Craft Tools English wheels, from 1987 to 2010, first unit was sold to Robert Yates, and the last one was traded to Robert Yates to get the first back, the irony in this sport. Another fun fact for every English wheel sold (complete or kit form) by Metal Craft Tools my dad sent John Glover $10 for that wheel’s plans.

Once my dad sorted out the manufacturing process for John’s dies in 1988, he was the only one selling a 44-inch floor model English wheel. As the NASCAR industry caught on to shaping the skins, Metal Craft Tools cornered the market. Cal Davis introduced several videos of John Glover teaching techniques on the English wheel, biggest issue is like a multiple of other skills, it is 10% instruction 90% applied practice.

By 1989 dad built several teaching aides a developed a curriculum for teaching racers the methodology of hanging a NASCAR metal body this included building panels with the English wheel. 10 per class, 5 English wheels per class to work on. Wheeling panels with the English wheel you will hear is an art, truth is understanding what the equipment is capable of and using it to do what it is attended to do is a skill. In the early days of wheeling in NASCAR there was a ton of wasted labor, I have seen guys spend 12 hours on a pair of front fender half’s, on the other side of that coin seen dudes with shrinker and wheel fab a set just as good in 4 hrs. The trick was not losing control of the panel, over stretching a spot then having to stretch the rest of the panel wasn’t cost efficient. Reading a panel is the art, being able to duplicate parts fast is profitable. I understand the De Havilland manufacturing business model that had cheap labor doing menial task, they were not invested in the structure, and the fitters were only interested in covering the hole with parts that allowed them to finish rivet panels on the edges. By 1990 Metal Craft Tools added several tool lines, branched out to the aviation market. By now the carpet baggers were copying the business model. My dad had learned a few hammer techniques, one was stack shrinking, the excepted concept of shape was stretch by thinning metal, this also work hardened the parent metal, stack shrinking was a process were the metal thickened and had the opposite effect softening the metal. My dad’s direction soon changed to the power hammer that’s another tool review. John’s dad’s lifelong friend had a saying wheelers have flat thumbs, but hammer heads couldn’t hear!

The Mechanics of the English Wheel

I can remember seeing pictures of car shops from England the old Morgan factory, Rolls Royce shops, the De Havilland aircraft factory where they would have just hundreds of cast iron English wheels lined up. Folks would make parts and fitting to different wooden bucks for the airplanes and for the cars, at the time it was very cost effective because labor was cheap and the training process for teaching folks to use an English wheel were very simple. If they could comb their hair, if they could brush their teeth, if they had any rhythm at all they could use an English wheel. The mechanics behind the English wheel were never the issue of the day. My grandfather told me in WWII there was just enough fear in the air that the process and the associated skill were never questioned but applied with vigor. As we entered into the business John Glover had come up with a simple plan for a 48-inch English wheel, as I got into the Winston cup racing and I got the opportunity to spend a number of days in the wind tunnel on 10 mile Rd in GMs Detroit tech center. The wind tunnel they had a couple of these design English wheels that had been built by John Glover. We got the opportunity to play with them, use them to shape stuff, to make things, even though we had never seen one, we excepted the concept, you know this was in the mid-1980s.

I asked John Glover one time does the English need to be stiff, or does it need to have flex in it or does it need 2000 psi or 5000 psi. John had a simple answer he said the English wheel shapes metal you use your rhythm and control to put that shape in it, he said the stiffer the wheel is, the quicker it will move the metal, but it’ll also work harden the metal faster and stop shaping, he says it will stretch it from point A to point B faster, but it will get the point B it will stop moving, the amount of shape is the issue. John didn’t reference the English wheel as stiffer or as a softer, English wheels that had more flex in it, he called it lazy, his terminology was based on patience and time, he used to call it sneaking up on a panel. Sneaking up on a panel is cost efficient. The upper wheel changed the mass in motion attack, solid billet in honesty was cheaper to build, as in anything with wheels the larger diameter is smoother but heavier making it harder to change directions.

The cast uppers are a gift when you spend 40 hours a week wheeling, but from a manufacturing point are more labor extensive with a greater chance of blank issues. Casting your own gives you better control of material and machining time.

The 9” lightweight billet is by far the best product. Chasing everything from 1020 to 4340 we found that if you want your ancestors to appreciate your English wheel as artifact that the 4340 HT is the way to go, in honesty the 1020 is more than efficient to get the job done. When you evaluate all the properties based on good engineering practices, availability, cost, the projected life of product will outlive most zombies.

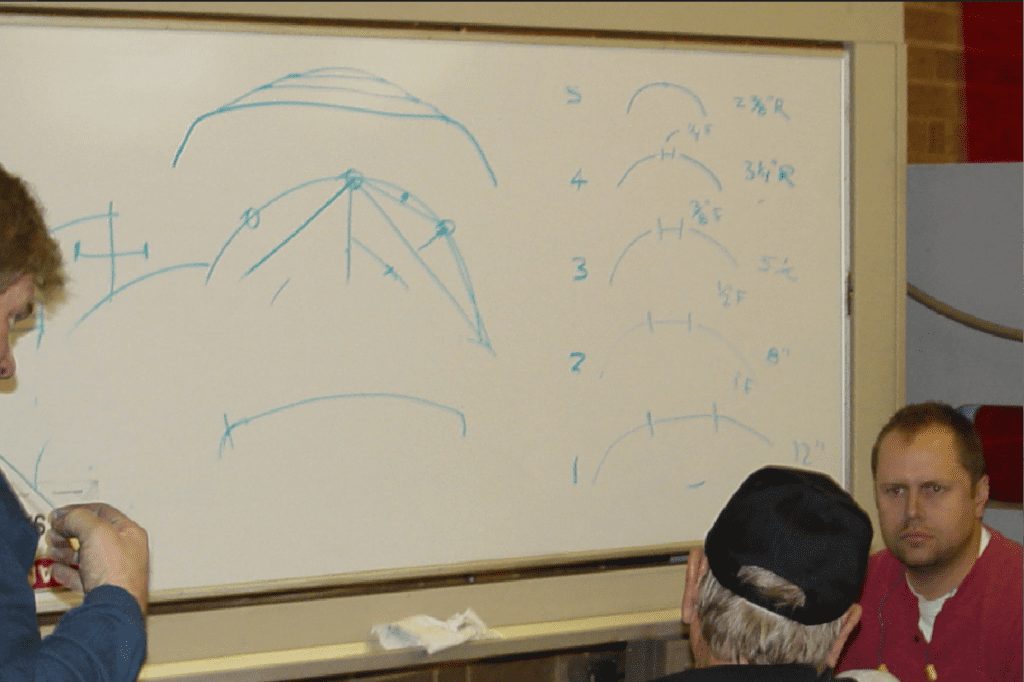

English Wheel lower dies have always been listed as one of the 7 wonders of the world. I have seen multiple configurations, and even custom dies for special applications. People are quick to assume EW lower dies are perfect radius’, I have seen thousands of perfect radii dies. Dads metal shaping students got the low down on the EW lower dies he manufactured; above is the drawing he drew probably 500 times in his lifetime. The English Wheel’s magic is mechanical in nature, applied pressure creates stretch, the contact area is the point of change. A true radius dies touch at one point, tighter the radius smaller the affected area, still a point at best. True radius dies can shape metal and the skirts of the dies control the maximum shape like the skirts on dies with flats. Year’s ago, word got out Dad drew his dies on the board, a competitor from Indiana sent an employee to the metal shaping class to get a picture, not even two days later a manufacturer from Alabama, went online to challenge dad saying his drawing was of his dies. I am impatient when shaping, I don’t like wheeling for hours to get there, hate to hammer in a lead bag, put in the sharpest radius die, shrink the edges, go for it. John Glover said the proper way was to sneak up on a panel, ain’t no sneak in me. The wider the flat the more time it takes to shape, the flat upper controls the direction of the shape, the stiffer the frame of wheel, the more pressure per square inch. A flat has an affective point of contact that stretches/shapes the metal, work hardening the material as it goes. I have had the opportunity to see some of the best in the business shape panels with an English Wheel, material awareness is a part of the illusion.

After spending a good portion of my life as a custom body man, painter, and fabricator building performance vehicles my experience as a metal shaper is very proficient, I have personally trained over 1500 individuals to develop exterior body panels for cars and aircraft using the English wheels and power hammers. Over the years I have used just about every version and or configuration of the English wheel. At the end of the day, I can say I have only used one or two English wheels in my life that would stopped me from making a successful panel, my take is simple that any English wheel using measurable patterns of systematic stretching can produce panels. I told John that I felt English wheels were like snowflakes, everyone has their own personality, he told me when he first started, he tried to use the same wheel every day because he thought in time it would improve his repeatable success, he even had his own set of dies. He later told me good metal shapers just use the tools at their deposal get the job done placing more value on skill, less on the excuse of the equipment. As an manufacturer we were always pushed to address the English wheel in a scale of rigidity, while the real test was range of work area, stability/ weight, mobility, quality of fabrication, alignment of the die centerlines, X, Y, Z parallels, diameter of upper wheel, diameter of lower dies, the side radius of dies, blend radius, the contact width, the material, die finish and duty cycle based on 40 hr. wk., 2080 hours per year. When we started Metal Craft Tools, dad being an engineer and machinist precision was important, as in many situations involving engineers they tend to exaggerate the importance of the machine, 21st century precision for a tool that had been used since the 1800’s. When evaluating equipment determining the duty cycle vs cost is a mental exercise, I always challenge shop owners to think about it. A 5-year pc of equipment that cost $5000, $1000 per year, 40 hrs. a week x 52 weeks cost about $.50 per hour to hang your coat on. Shop rates for metal shaping is about $100 per billable hour, in most cases a 40-hr. work week is about is about 25 billable hours or $62.50 per clock hour. $5000 piece of equipment should be paid out in a few weeks. Most weldment style English wheel have a fatigue life of 20 years, since 1987 I have seen more fatigue issues with cast frames than American tube weldments. A solid works study we chased in 2010 established factor of safety on a number of American Vs Chinese design English wheels, we found huge swings in tube thickness and die material hardness in Chinese weldments. Using best engineering practices (CAD FEA’s) that includes but is not limited to life (duty cycle), tasks/ loads (shaping panels) material (thickness, hardness) each of the English wheels passed the with a minimum of 2 to 1 factor of safety for constant use 5 years, 2080 hours per year. Some of our closest competitors were marketing their English wheels and continue to do so as a super engineered extension of their manhood, the truth is it is a simple tool. In 1987 we costed the Metal Craft Tools English wheel using the following formula, raw material cost ($500)+ shop rate labor($500 10hrs x $50) +R&D ($500 5hrs x $100) + Profit (30%/ 1.50X) Dealer Markup(10%/ 1.12x) for $2500 retail price. We held the price at $2500 until dad retired in 2010.

The Metal Craft Tools bench top English wheel was introduced in 1992 and was a very affordable scaled model of the 44” English wheel. Although scaled the benchtop wheel was stiff at best, moved metal fast, it had a steeper learning curve to be smooth, in some applications it was easy to lose the panel, and hard to regain control. The bench top wheels worked good for one off projects, art, armor, motorcycle tanks, repair panels. The price for the Bench top was raw material ($250) +shop rate labor ($250 5 hrs. x $50) + Profit(30% / x1.5) = $750 retail price. From 1992- 2010 Metal Craft Tools sold a 3 to 1 ration of bench top wheels to every full size 44” English wheel or 44” kit. In 2010 dad made a deal with Mike Mittler to take over the production of the Metal Craft Tools English wheels and Power Hammer. Dad and Mike compared the English wheels frames/ dies/ production procedures, at the end of the day they agreed to offer the baseline John Glover lower die configurations and both the upper 9” and 8” dies.

English Wheel Amazon Market Review

Based on the information provided on each product listed under the English Wheel search on Amazon. There are 11 products represented, 6 that fall into private label categories w/similar design features, 4 bench top category, 2 with upper die options. Lowest cost is $291, Highest cost is $10,169. Our team chose 3 affordable options for home hobbyist, semiprofessional racer, restoration shop or artist. Our evaluation included availability, frame design and construction, listed die materials and moving mechanism design. Each of the choices surpassed the 5-year service cycle estimate:

1: JEGS 81516 English Wheel with Anvils

2: Baileigh EW-28 English Wheel

Baileigh EW-37HD Heavy Duty English Wheel

Eastwood Benchtop English Wheel

Eastwood Elite Heavy Duty English Wheel